What is social identity theory anyway?

Today I want to discuss social identity theory. Why? Because it’s important in so many aspects of our lived experience of work. And of life outside of work too, really in any context where humans and, in particular, groups of humans are involved. And once we know about this tendency within ourselves as human beings, we’re better able to do something positive with it. Perhaps to avoid the extremes of view that it might lead to and instead to get value from it. For the good of everyone.

Social identity theory was a concept originally put forward by Henry Tajfel and John Turner in the late 1970s and developed in the 1980s. I know, two middle-class white dudes as usual, but this is actually an idea that applies to us all. Social identity theory tells us that we adopt different identities depending on the social group we perceive ourselves to be part of. And we do this because we are motivated towards a sense of self-worth and self-esteem (and being part of a social group can support this). We are also motivated towards existing as social beings (presumably because, from an evolutionary perspective, there is perceived safety in numbers, and so being part of a group keeps us safer than being an outsider).

Summary so far: we have various social identities, and they are cued by our social context. At work, sometimes our identity will come from seeing ourselves as a member of our company (say if we’re at a conference or working with a client). Or our department (if we’re at an all-hands cross-company meeting, say). Or our team (if we’re working in a matrix setting). Outside of work, we could see ourselves as, variously, a parent, sports team supporter, a runner, a sibling, or whatever the group might be. The theory goes that because we are social animals, we then adopt the stereotypical characteristics of the group when we’re amongst them so that we can positively distinguish ourselves from those outside the group, feel good about ourselves, and feel safe and protected.

At the other end of the social identity spectrum is your personal identity. Your personal identity is you on your own in a safe environment with no social context. It’s authentic ‘at home’ you. Your ‘shoes off’ self. You’re safe, but you’re not part of a social group so you can behave like no one’s watching. Because no one is.

How is this relevant to the world, to society and conflict?

OK, so most of the time, social identity theory works for us. It makes us feel good about ourselves; we feel part of something relevant and important, and we feel safe. But sometimes, particularly when we perceive our group is being threatened or when we allow our socially protective tendencies to go too far, our social identities can lead to outcomes that aren’t necessarily positive for everyone. And sometimes, for anyone!

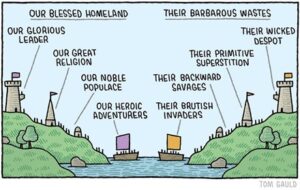

Let’s take an international conflict, for example. In this situation, while people on both sides of the conflict know that everyone involved is still human, it serves the groups in conflict to see their own group favourably and to see the group they are fighting in negative ways. For social psychologists, this is known as ‘ingroup favouritism’ and ‘outgroup derogation’. So, although when we’re not threatened or in conflict, we tend to focus on characteristics that we have in common, when we inject the stress of conflict into the equation, we are likely to see our views as being morally right and ‘their’ views as morally wrong or corrupt. We will be more likely to agree with other members of our group and more likely to disagree with members of the other group. In the blog version of the podcast over on the Strengthscope website, Resources page, I’ve included a graphic from the Simply Psychology website that illustrates this perfectly, drawn by an illustrator called Tom Gauld.

How language is used to create a sense of ‘them and us’ which can define history

How is social identity theory relevant to work, then?

This all feels like important stuff at the societal level, but how is it relevant to work? Let me draw some connections with our experience of teams, organisations and even leadership.

Firstly, teams–outgroup derogation and ingroup favouritism can lead to a whole variety of outcomes. Some positive, some not so much. On the one hand, this drive within us can lead us to behave positively towards other members of our group. To look out for other people, care about them, advocate for them, listen to their views and create an even stronger social bond. But when taken to an extreme, it can lead to what’s called ‘groupthink’, which creates a narrow, insular focus, where everyone is assumed to have similar views and anyone from the group who disagrees is isolated or even removed as a threat. This clearly has implications for diversity of thinking, encouraging positive challenge in groups, and creating genuine psychological safety for everyone in a group.

Secondly, when it comes to organisations – social identity theory in its positive form can lead to a feeling of engagement, connection and instil a desire to advocate for the place you work and for the team and department you work in. But too much of this good thing can lead to the creation of departmental and team silos, and in organisations where it’s rife, particularly organisations which have grown through acquisition, it creates inefficiency, rework, a lack of trust and a hyper-competitive environment with lots of infighting and very little space for collaboration, co-creation or shared learning.

Finally, let’s turn to leadership – Social identity theory is important for leaders because if you haven’t done the work on your own leadership identity, that is, if you haven’t established what makes you positively different as a leader…focusing on the question why should anyone follow you as a leader, you may well adopt the characteristics of a leader based on what you believe a leader should look and act like. Without working on how you want to intentionally show up as a leader, there may well be a disconnect. You may look like a cookie-cutter version of a leader (as you will have adopted stereotypical behaviours of leaders you admire or which you see in your current organisation) and not your own version. And people can tell; they will sense it and see it, as they will see a disconnect between what you say and how you act.

OK, so much for the risks created by social identity theory in overdrive. What do we do about it?

Let’s take teams first – how can we avoid the downside of social identity theory and create ‘sticky teams’ that people don’t want to leave without inadvertently creating a cult where only the conformists can survive? There are several things to focus on. One of the most helpful is to cultivate ‘integrative complexity’, which can lead to greater diversity of thought. Integrative complexity is a thinking style characterised by a willingness to consider a range of competing ideas as valid and legitimate. This approach has the benefit of enhancing the skills we need in order to work with people we disagree with whilst not requiring anyone to change their views. And it can lead to richer conversations within a group, as well as encouraging collaboration within and across teams, departments and organisations. BTW, imagine how helpful that could be when international conflicts kick-off.

For more on what you can do to create positive, cohesive teams that aren’t likely to get themselves into a silo mindset, have a listen to Season 10, episode 5 ‘Diversity of thought for leadership teams’ and also Season 12, episode 5, ‘What is psychological safety and how can you get it?’.

Next, let’s have a look at organisations. Here are some thoughts on getting the best from social cohesion without seeing the worst in terms of hyper-competition. First, you can cultivate inclusive values. What I mean by this is creating a culture which genuinely enables people to show up as themselves, express their views freely and not demonise any individual or group simply because they state views that you don’t agree with. Second, it’s worth encouraging dialogue and human-to-human connection across groups and perceived divisions within organisations to stimulate genuine human connection, understanding and can create the conditions for true collaboration even when (and actually because) points of difference exist. Organisations are more effective when they encourage diverse thinking.

Finally, leadership – as a leader, your task here is to develop your own unique leadership brand based on your points of positive difference. Ask yourself what kind of leadership identity do you want to develop, which casts an intentional shadow of your own making and which reflects at least some elements of your personal identity. If you share none of that what makes you uniquely ‘shoes off’ you, the one who dances like no one’s watching, you risk being seen as inauthentic and just a template leader, rather than relatable and accessible and someone that others would want to follow. You need to craft your own leadership identity and brand and then make sure that others would describe you in the same way as you would want when you’re not in the room.

Conclusion – we can get the best from social identity theory and not just resign ourselves to the worst

I know that psychology can sound like common sense sometimes. And that there’s probably nothing new that I’ve shared with you in terms of knowledge that humans tend to hang about in groups and tend to behave differently when they’re in different groups. But when you start to take that information and realise the catastrophic consequences that can have in society…as I speak, the increase in anti-Islamic and anti-Semitic hate crimes in the UK as a result of the conflict between Israel and Palestine is horrifying…and start to consider what we can do in our own lives and organisations to harness this force for good, hopefully, you can see that there’s a genuinely important learning point here. Till next time. Stay strong.